You are currently browsing the daily archive for July 22, 2009.

Huh — no solutions to POW-13 came in! I guess I was surprised by that.

Ah well, that’s okay. The problem wasn’t exactly trivial; there are some fairly deep and interesting things going on in that problem that I’d like to share now. First off, let me say that the problem comes from The Unapologetic Mathematician, the blog written by John Armstrong, who posted the problem back in March this year. He in turn had gotten the problem from Noam Elkies, who kindly responded to some email I wrote and had some pretty insightful things to say.

In lieu of a reader solution, I’ll give John’s solution first, and then mine, and then touch on some of the things Noam related in his emails. But before we do so, let me paraphrase what John wrote at the end of his post:

Here’s a non-example. Pick

points

and so on up to

. Pick

points

,

,

, and so on up to

. In this case we have

blocking points at

,

, and so on by half-integers up to

. Of course this solution doesn’t count because the first

points lie on a line as do the

points that follow, which violates the collinearity condition of the problem.

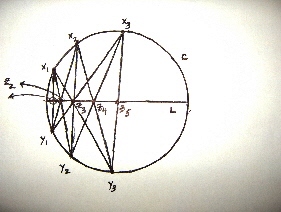

Here’s a picture of that scenario when :

Does this configuration remind you of anything? Did somebody say “Pappus’s theorem“? Good. Hold that thought please.

Okay, in the non-example the first points were on two lines, which is disallowed. Now the two lines here,

and

, form a degenerate conic

. Thinking in good algebraic geometry fashion, perhaps we can modify the non-solution by replacing the degenerate conic by an honest (smooth) nondegenerate conic, like an ellipse or something, so that at most two of the

points are on any given line. This should put one in the mood for our first solution.

John Armstrong writes: Basically, I took the non-example and imagined bending back the two lines to satisfy the collinearity (pair-of-lines = degenerate conic, so non-example is degenerate example). The obvious pair of curves to use is the two branches of a hyperbola. But hyperbolas can be hard to work with, so I decided to do a projective transformation to turn it into a parabola.

The line itself is . Which has the obvious

-intercept

. Now we need to pick a lot of

and

values to get repeated products. Place

points at

,

,

,

, and so on above the negative powers of two. Place

points at

,

,

,

, and so on above the positive powers of two. The blocking points are then at

,

,

,

, and so on up the

-axis by powers of two. Presto!

Very nice. My own solution was less explicit in the sense that I didn’t actually write down coordinates of points, but gave instead a general recipe which relies instead on the geometry of conics, in fact on a generalization of Pappus’s theorem known to me as “Pascal’s mystic hexagon“. I first learned about this from a wonderful book:

- C. Herbert Clemens, A Scrapbook of Complex Curve Theory (2nd Edition), Graduate Studies in Mathematics 55, AMS (2002).

Pascal’s Mystic Hexagon, version A: Consider any hexagon inscribed in a conic, with vertices marked . For

, mark the intersection of the lines

by

. Then

are collinear. (The reason for the strange indexing will be clear in a moment.)

Pascal’s Mystic Hexagon, version B: Consider any pentagon inscribed in a conic , with vertices marked

. Choose any line

through

, and define

and

. Then the intersection

is the sixth point of a hexagon inscribed in

.

The following solution uses version B.

Solution by Todd and Vishal: For the sake of explicitness, let the conic be a circle

and let the line (segment)

be the diameter along

. Choose two points

on

above

and a point

on

below

. The remaining points are determined recursively by a zig-zag procedure, where at each stage

is the intersection

, where

, where

, and

. We will show the blocking condition is satisfied: for all

, the point

is on the line

.

To get started, notice that the blocking condition is trivially satisfied up to the point where we construct . Mystic Hexagon B ensures that

, as defined above, is blocked from

by

and from

by

. Then define

as above. So far the blocking condition is satisfied.

Suppose the blocking condition is satisfied for the points . Define

, as above. Then Mystic Hexagon B, applied to the pentagon consisting of points

, shows that

is blocked from

by

and from

by

.

This shows that could have been defined to be

. Then Mystic Hexagon B, applied to the pentagon

, shows that

is blocked from

by

and from

by

. This shows

could have been defined to be

.

And so on up the inductive ladder: for , defining

, Hexagon B applied to the pentagon

shows that

could have been defined to be

. This shows the blocking condition is satisfied for

,

. We block

from

by defining

as above, to extend up to

.

Then, as prescribed above, we define , and repeat the preceding argument mutatis mutandis (interchanging

‘s and

‘s), to obtain the blocking conditions up to

,

. This completes the proof.

What this argument shows (with Hexagon B doing all the heavy lifting) is that no cleverness whatsoever is required to construct the desired points: starting with any nondegenerate conic , any secant line

, and any three initial points

on

to get started (with

‘s on one side of

and

on the other), the whole construction is completely forced and works no matter what!

Which may lead one to ask: what is behind this “miracle” called Pascal’s Mystic Hexagon? Actually, not that much! Let me give a seat-of-the-pants argument for why one might expect it to hold, and then give a somewhat more respectable argument.

Define a planar cubic to be the locus of any degree 3 polynomial

in two variables. (We should actually be doing this as projective geometry, so I ought to write

where

is homogeneous of degree 3, but I think I’ll skip that.) For example, the union of three distinct lines is a cubic where

is a product of three degree 1 polynomials. What is the dimension of the space of planar cubics? A cubic polynomial

,

has 10 coefficients. But the equation is equivalent to the equation

for any nonzero scalar

; modding out by scalars, there are 9 degrees of freedom in the space of cubics. What is the dimension of the space of cubics passing through a given point

? The condition

gives one linear equation on the coefficients

, so we cut down a degree of freedom, and the dimension would be 8. Similarly, if we ask for the dimension of cubics passing through 8 given points, we get a system of eight linear equations, and we cut down by eight degrees of freedom: in general, the space of cubics through 8 points is “expected” to be (is “almost always”) 1-dimensional, in fact, a (projective) line.

In the configuration for Pascal’s Mystic Hexagon, version A

we see three cubics passing through the 8 points , namely:

where the conic

is defined by a degree 2 polynomial

Since we expect that the space of cubics through these eight points is a line, we should have a linear relationship between the cubic polynomials used respectively to define

, and

above, hence we would get

for some scalars . Thus, if a ninth point

is in

and

, so that

, then

. Thus

lies in

as well, and if

isn’t on

, it must be on the line

. Thus, “generically” we expect

to be collinear, whence Hexagon A.

This rough argument isn’t too far removed from a slightly more rigorous one. There’s a general result in projective algebraic geometry called Bézout’s theorem, which says that a degree planar curve and a degree

planar curve either intersect in

points (if you count them right, “with multiplicity”) or they have a whole curve component in common. (Fine print: to make this generally true, you have to work in the projective plane, and you have to work over an algebraically closed field.) A much weaker result which removes all the fine print is that a degree

curve and a degree

curve either have a curve component in common, or they intersect in at most

points. In particular, in the notation above, the cubics

and

intersect in 9 points, 6 of which are on the conic

. Pick a seventh point

on

, away from those six, and let

and

. Then we see that the locus of the degree 3 polynomial

intersects the degree 2 conic in at least 7 points (namely,

and

), greater than the expected number

, which is impossible unless the loci of

and

have a component in common. But the conic

has just one component — itself — so one can conclude that its defining degree 2 polynomial (I’ll call it

) must divide

. Then we have

for some degree 1 polynomial , so the last three of the nine points of intersection

, which are zeroes of

and

, must be zeroes of the linear polynomial

, and hence are collinear. Thus we obtain Pascal’s Mystic Hexagon, version A.

It’s clear then that what makes the Mystic Hexagon tick has something to do with the geometry of cubic curves. With that in mind, I’m now going to kick the discussion up a notch, and relate a third rather more sophisticated construction on cubics which basically subsumes the first two constructions. It has to do with so-called “elliptic curves“.

Officially, an elliptic curve is a smooth projective (irreducible) cubic “curve” over the complex numbers. I put “curve” in quotes because while it is defined by an equation where

is a polynomial of degree 3, the coefficients of

are complex numbers as are the solutions to this equation. We say “curve” in the sense that locally it is like a “line”, but this is the complex line

we’re talking about, so from our real number perspective it is two-dimensional — it actually looks more like a surface. Indeed, an elliptic curve is an example of a Riemann surface. It would take me way too far afield to give explanations, but when you study these things, you find that elliptic curves are Riemann surfaces of genus 1. In more down-to-earth terms, this means they are tori (toruses), or doughnut-shaped as surfaces. Topologically, such tori or doughnuts are cartesian products of two circles.

Now a circle or 1-dimensional sphere carries a continuous (abelian) group structure, if we think of it as the set of complex numbers

of norm 1, where the group operation is complex multiplication. A torus

also carries a group structure, obtained by multiplying in each of the two components. Thus, given what we have said, an elliptic curve also carries a continuous group structure. But it’s actually much better than that: one can define a group structure on a smooth complex cubic

(in the complex plane

, or rather the projective complex plane

) not just by continuous operations, but by polynomially defined operations, and the definition of the group law is just incredibly elegant as a piece of geometry. Writing the group multiplication as addition, it says that if

are points on

, then

if are collinear. [To be precise, one must select a point 0 on

to serve as identity, and this point must be one of the nine inflection points of

. When

and

coincide (are “infinitesimally close”), the line through

and

is taken to be tangent to

; when

coincide, this is a line of inflection.]

This is rather an interesting thing to prove, that this prescription actually satisfies the axioms for an abelian group. The hardest part is proving associativity, but this turns out to be not unlike what we did for Pascal’s Mystic Hexagon: basically it’s an application of Bézout’s theorem again. (In algebraic geometry texts, such as Hartshorne’s famous book, the discussion of this point can be far more sophisticated, largely because one can and does define elliptic curves as certain abstract 1-dimensional varieties or schemes which have no presupposed extrinsic embeddings as cubic curves in the plane, and there the goal is to understand the operations intrinsically.)

In the special case where is defined by a cubic polynomial with real coefficients, we can look at the locus of real solutions (or “real points”), and it turns out that this prescription for the group law still works on the real locus, in particular is still well-defined. (Basically for the same reason that if you have two real numbers

which are solutions to a real cubic equation

, then there is also a third real solution

.) There is still an identity element, which will be an inflection point of the cubic.

Okay, here is a third solution to the problem, lifted from one of Noam Elkies’ emails. (The original formulation of the problem spoke in terms of “red” points (instead of my

),

“blue” points (instead of my

), and “blocking” points which play the role of my

.) The addition referred to is the addition law on an elliptic curve. I’ve taken the liberty of paraphrasing a bit.

“Choose points on the real points of an elliptic curve such that

is in-between

and

. Then set

- red points:

,

- blue points:

,

- blocking points:

,

where is a real point on the elliptic curve very close to the identity. The pair

,

is blocked by

, because these three points are collinear, and the smallness of P guarantees that the blocking point is actually between the red point and blue point, by continuity.”

Well, well. That’s awfully elegant. (According to Noam’s email, it came out of a three-way conversation between Roger Alperin, Joe Buhler, and Adam Chalcraft. Edit: Joe Buhler informs me in email that Joel Rosenberg’s name should be added. More at the end of this post.) Noam had given his own slick solution where again the red and blue points sit on a conic and the blocking points lie on a line not tangent to the conic, and he observed that his configuration was a degenerate cubic, leading him to surmise that his example could in a sense be seen as a special case of theirs.

How’s that? The last solution took place on a smooth (nondegenerate) cubic, so the degenerate cubic = conic+line examples could not, literally speaking, be special cases. Can the degenerate examples be seen in terms of algebraic group structures based on collinearity?

The answer is: yes! As you slide around in the space of planar cubics, nondegenerate cubics (the generic or typical case) can converge to cubics which are degenerate in varying degrees (including the case of three lines, or even a triple line), but the group laws on nondegenerate cubics based on collinearity converge to group laws, even in degenerate cases! (I hadn’t realized that.) You just have to be careful and throw away the singular points of the degenerate cubic, but otherwise you can basically still use the definition of the group law based on collineation, although it gets a little tricky saying exactly how you’re supposed to add points on a line component, such as the line of conic+line.

So let me give an example of how it works. It seems convenient for this purpose to use John Armstrong’s model which is based on the parabola+line, specifically the locus of . The singular points of its projective completion are at

and the point where the

-axis meets the line at infinity. After throwing those away, what remains is a disjoint union of four pieces: right half of parabola, left half of parabola, positive

-axis, negative

-axis.

We can maybe guess that since implies

collinear, that the two pieces of the

-axis form a subgroup for the group law we are after (also, these two pieces together should suggest the two halves of the multiplicative group of nonzero reals

, but don’t jump to conclusions how this works!). If so, then we notice that if

and

lie on the parabola, then the line between them intersects the

-axis at a point

, so then the parabolic part would not be closed under multiplication.

One is then led to consider that the group structure of this cubic overall is isomorphic to the group , with the linear part identified somehow with the subgroup

, and the parabolic part with

.

I claim that the abelian group structure on the punctured -axis should be defined by

so that the identity element on the cubic is , and the inverse of

is

. The remainder of the abelian group structure on the cubic is defined as follows:

Undoubtedly this group law looks a bit strange! So let’s do a spot check. Suppose ,

, and

are collinear. Then it is easily checked that

, and each of the two equations

is correct according to the group law, so the three collinear points do add to the identity and everything checks out.

All right, let’s retrieve John’s example as a special case. Take as a red point,

as a blue point, and

as blocking point. Take a point

“sufficiently close” to the identity, say

. Then

which was John’s solution.

Another long post from yours truly. I was sorry no solutions came from our readers, but if you’d like another problem to chew on, here’s a really neat one I saw just the other day. Feel free to discuss in comments!

Exercise: Given a point on a circle, show how to draw a tangent to the point using ruler only, no compass. Hint: use a mystic hexagon where two of the points are “infinitesimally close”.

Added July 25: As edited in above, Joel Rosenberg also had a hand in the elliptic curves solution, playing an instrumental role in establishing some of the conjectures, such as that is the minimal number of blocking points under certain assumptions, and (what is very nice) that the elliptic curves solution is the most general solution under certain assumptions. I thank Joe Buhler for transmitting this information.

Recent Comments